Population pressure and climate change are forcing more communities in the US and abroad to rely on degraded water sources containing complex contaminant mixtures. We must rethink how we prioritize contaminants for regulation and how we design drinking water treatment trains to mitigate public health risk. The proliferation of water reuse, both planned and de facto, poses a special set of challenges but also provides opportunity for reinvention.The overall goal of our research is to develop policy and engineering strategies to minimize the health risk posed by contaminant mixtures in drinking water.

Water systems chemistry

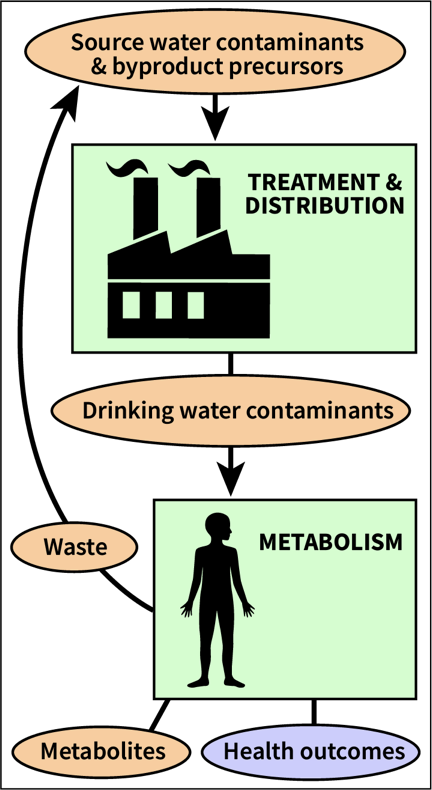

We have projects that address the transport and fate of organic contaminants across the three main compartments of the drinking water cycle: 1) Source water which is impacted by various stressors; 2) The engineered aquatic environment (treatment and distribution); 3) The human-water interface. Although we have projects that focus within one of these compartments, increasingly we are taking a "systems approach" to explicitly connect these compartments in order to discover transformative engineering and policy solutions for mitigating exposure to complex organic contaminant mixtures.

Equitable engineering solutions

Our research is guided by the principles of Universal Design, which holds that designing solutions that work for people on the margins often results in solutions that work better for everyone. A major thrust of our work focuses on understanding exposure conditions in low-income communities and developing low-cost engineering interventions that work for all.

Disinfection and disinfection byproducts

A lot of our work focuses on disinfection byproducts (DBPs), which are a major concern for human exposure in conventional drinking water and reuse systems. Disinfection is critical to protect against pathogenic microbes, but has the unfortunate side effect of forming DBPs. DBPs occur at higher concentrations and are thought to be more potent toxins than most other drinking water contaminants (e.g., pharmaceuticals). Unfortunately, they are also more difficult to remove than most other contaminants. They form in essentially all disinfected drinking waters, which means most of us are regularly exposed to them via ingestion and showering/bathing. DBPs are associated with bladder cancer, birth defects, and other human health problems, but we don’t yet know which of the >700 DBPs identified are responsible.

Our lab is working on novel approaches to DBP exposure assessment in order to help epidemiologists

identify which DBPs drive human disease. We are also working to understand distribution system

phenomena that may impact DBP formation and the chemistry of novel disinfectants with the potential

to minimize DBP formation.

Furst Lab Spotlights

We believe the systems approach is the best way to solve the world's water issues. Keep reading to find out how.

Assistant Professor Kirin Emlet Furst vision for the lab ...

Even during a pandemic, the work continues.

GMU Land Acknowledgement